How to Combat Loss of Muscle Strength as You Age

“],”filter”:{“nextExceptions”:”img, blockquote, div”,”nextContainsExceptions”:”img, blockquote, a.btn, ao-button”},” renderIntial”:true,”wordCount”:350 }”>

The smoking gun, for me, is the hill sprint at the end of the workout. I can still keep up with some of my younger training partners on tempo runs and mile reps, but when it comes to hill blasts, I’m left in the dust. That kind of explosive power was in my wheels, but now that I’m in my 40s, those gears are gone.

I am not alone. Loss of muscle strength is one of the signs of aging in the 40s and beyond. That’s a problem, because strength is one of the things that can help determine whether you’ll be able to handle normal activities of daily living, such as climbing stairs and lifting yourself up from a chair, at your age. the latter. But scientists aren’t sure why energy declines so rapidly and inexorably as a person ages. A new study in Journal of Applied Physiology digs into this mystery, and its findings provide more information on how to protect against this loss of energy.

Why Muscle Strength Is Important

Let’s start with a definition: power is equal to speed times power. When we talk about muscle strength, we are talking about how much strength a muscle can have. When we talk about muscle power, we are talking about a combination of how much power we can use and how quickly we can use it. To climb a hill, jump on a box, or get up from the couch, you need to give power in bursts rather than slowly. And indeed, research over the years has found that strength is more important than strength in predicting whether older people are able to successfully navigate activities of daily living.

The problem is that the power starts to drop before the power, and continues to drop rapidly. A common estimate is that you lose 0.5 to 1 percent of your muscle mass per year once you’re on the wrong side of 40. Strength tends to follow the same path. On the other hand, muscle strength declines by 2 to 4 percent per year. It is not clear where the extra loss comes from: it could be that our brain is sending fewer signals to the muscles; signals may be disrupted as they are transmitted through the nervous system; or something in the muscle itself can change the way it contracts.

What the New Study Reveals

Researchers at Marquette University, led by Christopher Sundberg, tested a group of young people with an average age of 23; the elderly group with an average age of 70; and a group of very old adults with an average age of 86. The tests measured how much force the subjects could produce with their quadriceps, sitting with a bent knee and then trying to straighten as strongly as possible. Using the brain’s magnetic field and the muscle’s electrical current, the researchers were able to tease out how much the brain and nervous system contribute compared to the muscle itself.

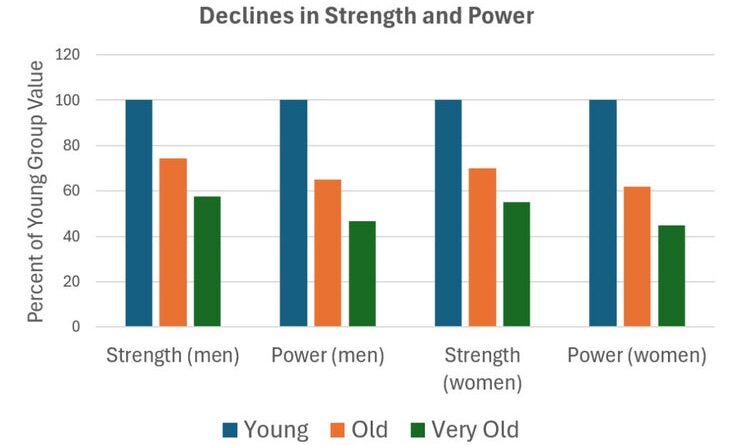

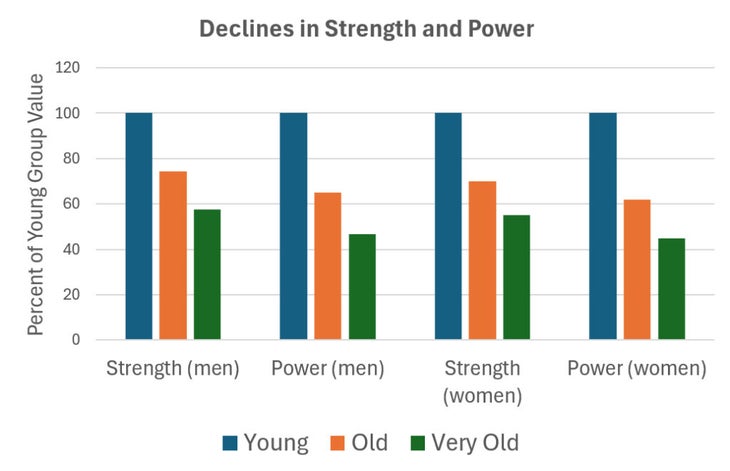

The data presented is somewhat complex and detailed (the tutorial is free to read online if you’d like to dig deeper), but the overall picture is clear. Here’s how strength and power density (divided by body weight) compare in three groups, for men and women:

There is no surprise here: you lose muscle strength with age, and as expected the decline in strength is greater than the decline in strength. But there did not seem to be a significant reduction in the ability of the brain and the nervous system to show significant shrinkage, even in the “very old” group. Instead, it was the muscle itself that did not contract as strongly as before.

There are many reasons why a muscle may lose its mobility. The muscle cells may be made up of fat and scar tissue, which prevents them from contracting properly. Tendons may be very weak, and therefore unable to transmit force as quickly. There may be changes in the chemistry of the muscle itself. One possible candidate, Sundberg and his colleagues suggest, is that we tend to lose more fast-twitch muscle fibers than slow-twitch fibers, leaving us with muscle. less and less in general.

What You Can Do About Reduced Muscle Strength

As with most aging studies, there’s a chicken-and-egg question here: am I slower at hill running because my muscles are changing, or are my muscles changing because I’m not doing hill runs and stuff? some that explode as often as possible? I used to? For aerobic exercise, one study I wrote last year estimated that only about half of the age-related decline is an inevitable result of aging, while the other half is caused by changed exercise routines. For muscle strength as well, the answer may be somewhere in the middle.

However, it is not just a general decline in performance. Participants in Sundberg’s study used an accelerometer to measure their daily step count as a rough estimate of their physical activity levels. There was almost no relationship between daily exercise and peak power: the number of steps explained only 3 percent of the variance in peak power. I’m an aerobics fan, but staying fit doesn’t seem to be enough to keep those muscles firing.

I continue to go over what the study found, but the message I take from it is that if you want to hold as much explosive power as possible, you need to move and train in explosive ways. Plyometric exercises, which include things like box jumps and pull-ups, are one method. Another option is resistance training at light weights—less than 60 percent of your one-rep max, according to the American College of Sports Medicine—where you focus on performing the movement. as soon as possible.

For the specific purpose of holding your fast fibers, there may be a case for doing heavy resistance training, with sets of six minimal reps. If the weight is heavy enough, you will need to hire your own speed ropes to lift it. It’s important to remember, after all, that power is speed times power – so increasing the power you’re able to deliver is an important part of the equation. There is evidence that once energy drops below critical mass, usable energy falls off the cliff.

Which of these different methods is most effective remains to be seen. For now, my plan is simple: more hill running.

For The Science of Sweat, connect with me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for my email newsletter, and check out my book Endurance: Mind, Body, and the Progressive Limits of Human Performance.

#Combat #Loss #Muscle #Strength #Age